A Critical Review of "The Preventive State"

Alan Dershowitz proposes a jurisprudence of the preventive state

I’m an frequent listener of Dershowitz’s podcast, The Dershow. Dershowitz has been encouraging his listeners to read his new book, The Preventive State: The Challenge of Preventing Serious Harms While Preserving Essential Liberties. I enjoyed the book and thought its goals and concerns important enough to write a critical review. I’ve always admired Dershowitz for his principled and objective support of fair legal standards and civil liberties and so I was disappointed that I didn’t agree with Dershowitz’s analysis or conclusions. Although not his intention, his proposals would tend to reduce rather than increase civil liberties. Still, the book is worth reading if you are worried that personal liberty is being smothered by the Leviathan.

In his new book, Dershowitz discusses the fundamental predicament that any constitutional democracy must resolve: how do you prevent people from harming others while not removing too much of their personal freedom? Dershowitz argues that despite the longstanding existence of the tradeoff between prevention and personal liberty, the legal system has developed no systematic jurisprudential framework to regulate the preventive state. Dershowitz’s aim is to begin to develop such a general framework, which he then concretely applies to criminal and civil procedures that result in confinement.

Dershowitz raises controversial and important policy issues that illustrate the tradeoff between personal liberty and prevention: free speech versus censorship; torture versus terrorism; red flag laws versus gun violence; and a host of others. His analysis of the tradeoff is hampered, however, by his underlying political philosophy: utilitarianism dressed up in a Rawlsian necktie. For Dershowitz, the rights that underpin personal liberty are not intrinsic or objective. Rights are merely empirically observed rules and conventions that we adopt to prevent the injustices that we have observed historically, subject to the Rawlsian fairness constraint that all rights should be enjoyed by everyone, regardless of their identities or positions in society.

The Rawlsian necktie can’t cover up the ugly utilitarianism underneath. Dershowitz’s underlying utilitarianism tilts the tradeoff towards less personal freedom. Dershowitz’s cost-benefit analysis, in which the costs of false convictions are weighed against the benefits of preventing crime, leads him to propose a weakening of legal protections against criminal accusations. His utilitarian obsession with outcomes-confinement is confinement-causes him to disregard the important differences between criminal and civil proceedings, leading to proposals that would fail to rectify the excessive civil confinements that regrettably often do occur. Dershowitz has always been a principled civil libertarian, but his proposed jurisprudential framework fails to adequately protect civil liberties.

Dershowitz’s Jurisprudence of Prevention

Dershowitz spends a good portion of the book framing the tradeoff in the statistical parlance of false positives and false negatives. In balancing freedom of speech against censorship, for example, a false positive would be censorship of speech that would not have caused any harm if it had been allowed, while a false negative is the failure to censor speech that did turn out to be harmful. In a red flag law, a false positive is taking a gun from someone who would not have used it illegally while a false negative is failing to remove a gun from someone who used it illegally. If the police shoot a fleeing suspect who would not have committed a crime if he escaped, that’s a false positive. But failing to shoot a fleeing suspect who subsequently commits murder in an armed robbery is a false negative.

Dershowitz focuses his concrete proposals on judicial procedures that may result in confinement or incarceration. He points out that there are many civil procedures that can result in confinement, which, if unjustified, is a false positive. He also points out that people can be jailed for long periods awaiting trial, another false positive if the defendant is not convicted. Alternatively, if defendants are not held and then commit more crimes while awaiting trial, that’s a false negative.

To develop a judicial framework that balances false positives and negatives, Dershowitz starts by arguing that the legal system irrationally distinguishes between preventive and punitive actions, providing more safeguards for punitive actions but not for preventive actions, even when preventive actions have the same result—involuntary confinement. Dershowitz claims that civil and criminal proceedings should not be distinguished if they achieve the same result—incarceration. However the balance between false negatives and positives is defined, it should be the same for any procedure that results in confinement, regardless of whether it’s a criminal or civil matter.

Standard of Proof

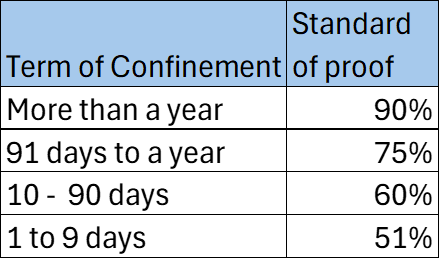

Dershowitz’s proposal is to quantify a common standard of proof for criminal or civil procedures that result in confinement. In his proposal, the standard of proof becomes stricter as the length of confinement increases, because the cost of a false positive-a mistaken confinement-rises with the length of the confinement.

In this case, Dershowitz defines “reasonable doubt” as being 90% confident that the defendant is guilty, so that confinement greater than a year implies proof must be beyond a reasonable doubt at a 90% confidence level. However, the standard of proof can be relaxed for shorter sentences. For periods of involuntary confinement between three months and a year, the standard of proof is 75% certainty, which roughly corresponds to the current clear and convincing evidence standard. Confinement for one to nine days corresponds to the civil standard of proof by preponderance of the evidence.

False Negatives Versus False Positives

Dershowitz proposes to set explicit tradeoffs between false negatives and false positives, motivated by the adage that it is better that ten guilty men go free than one innocent man go to prison. Ten guilty men going free is ten false negatives—ten cases of an acquittal when the defendant was guilty. One innocent man going to prison is one false positive—one case in which an innocent man was convicted. In this case, the judicial process would try to result in an outcome in which the ratio of false negatives to positives is ten.

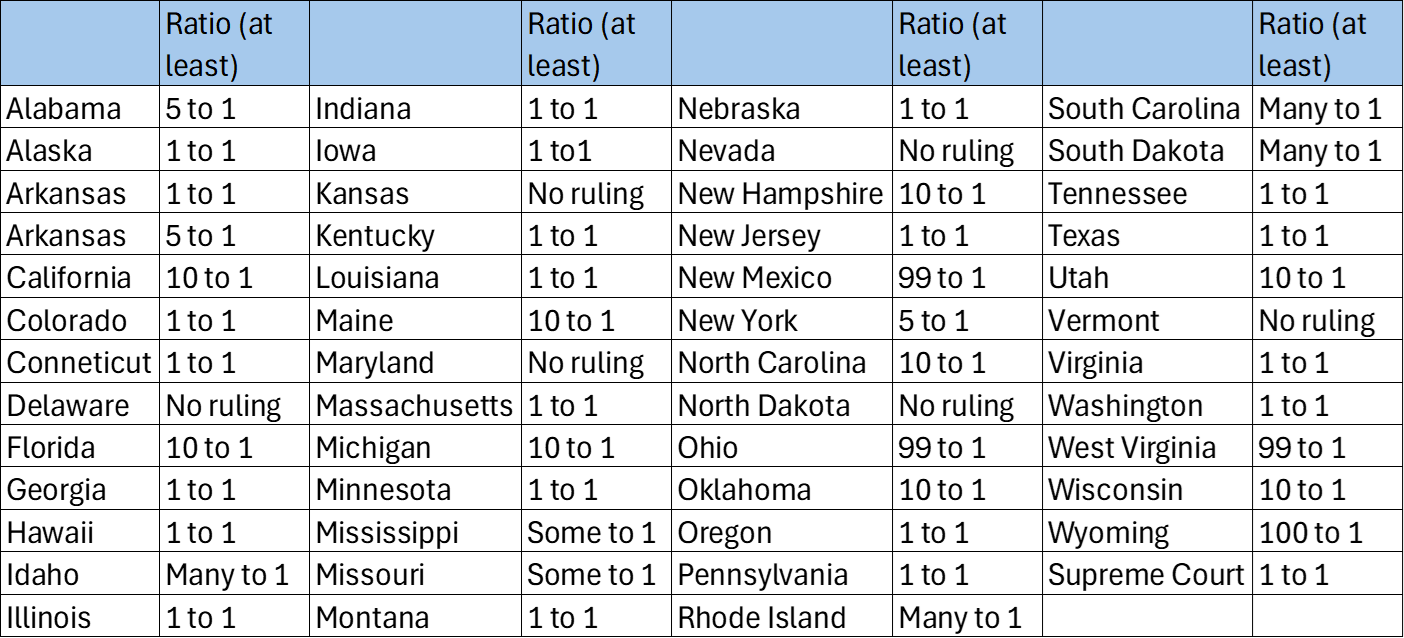

Readers familiar with criminal law will recognize that Dershowitz is advocating that Blackstone’s ratio, adjusted for the cost of false positives and negatives, be applied explicitly whenever a judicial process can result in confinement. The 18th century British Jurist William Blackstone famously suggested that “it is better that ten guilty persons escape than that one innocent suffer.” The Blackstone ratio has become a foundational principle in criminal law, although there is no agreement on the precise numbers. John Adams advocated a Blackstone ratio that “many” guilty persons should go unpunished for every innocent person who is punished. Benjamin Franklin assumed a Blackstone ratio of 100 to 1. The legal scholar Maimonides advocated a ratio of 1000 to 1 for capital crimes.

A definition of Blackstone’s ratio is even suggested in the Book of Genesis. As you may recall, God told Abraham that he would destroy the city of Sodom because it was filled with wickedness. Abraham bargained with God, asking how many innocent men would have to be found in the city for God to forbear destroying it. Abraham and God eventually agreed that ten innocent men would be sufficient. Since archeological records put Sodom’s population at between 600 and 1200, God was willing to allow between 590 and 1190 guilty men to go unpunished to avoid punishing ten innocent men, a Blackstone ratio between about 60 to 120 to one.

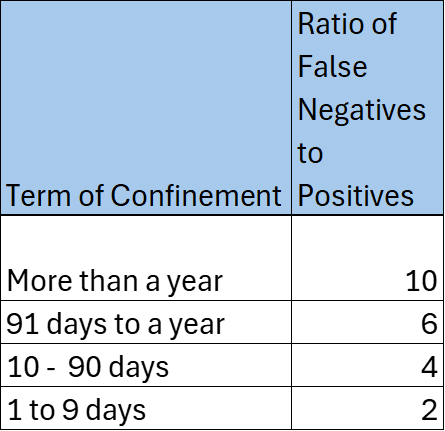

Dershowitz does not advocate setting a constant Blackstone ratio but rather one that depends on the costs of judicial mistakes. He does not attempt to measure costs precisely, but he does give some illustrative examples. The table below shows some representative ratios of false negatives to positives Dershowitz believes the legal system should target.

For confinement more than a year, Dershowitz advocates a judicial process outcome in which on average ten defendants guilty should go free for every defendant who is falsely confined. For periods below a year, the cost of falsely confining a defendant is smaller and so Dershowitz is willing to modify the target ratio to reflect the reduction in cost.

Will Dershowitz’s Proposals Protect Civil Liberties?

Legal Protection in Criminal Cases Would Be Reduced

All criminal procedures have some kind of “beyond a reasonable doubt” standard of proof that does not depend on the length of the potential sentence. Dershowitz’s proposals would reduce protections that criminal defendants already have.

The reasonable doubt standard was established in English jurisprudence by the end of the 18th century, when judges began to routinely instruct jurors that they should not convict if they have a “reasonable doubt” about the defendant’s guilt. In America, the first use may have been by John Adams in the Boston Massacre trials when he said “the best rule in doubtful cases, is, rather to incline to acquittal rather than conviction… If you doubt the prisoner’s guilt, never declare him guilty.” Thomas Paine argued that doubt in a criminal case must be also “reasonable.”

By the 20th century, the reasonable doubt standard was universally accepted by the courts, even though there is no reasonable doubt standard mentioned in the Constitution. In 1970, the Supreme Court clarified the constitutional status of reasonable doubt in In re Winship, holding that the due process guarantees of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments “protect the accused against conviction except upon proof beyond a reasonable doubt of every fact necessary to constitute the crime with which he is charged.”

Proof beyond a reasonable doubt for any crime, regardless of potential sentence, is a bedrock of the American legal system. But Dershowitz proposes to reduce the protections already afforded to criminal defendants.

Can Criminal and Civil Procedures Be Distinguished?

A crucial pillar of Dershowitz’s framework is that civil and criminal incarceration can’t be legally distinguished. To justify his view, he rejects Chief Justice Rehnquist’s arguments in the 1986 Supreme Court case, United States v Salerno, which allows pre-trial detention using a lower standard of proof than required in criminal trials.

Rehnquist, writing for the majority, argued that Congress can decide to confine people for regulatory reasons, such as for preventing crimes, or for punitive reasons. Courts should differentiate these cases by establishing what Congress intended. Rehnquist argues that higher standards of evidence would apply when Congress intended the confinement to be punitive. Thus, defendants who pose a danger to the community could be confined pre-trial if the purpose is to prevent additional crimes. Rehnquist noted that the right to a speedy trial should prevent defendants from being confined too long under the lower standard of evidence.

Dershowitz counters that Congressional intent doesn’t matter: involuntary incarceration is still objectively punishment regardless of what Congress intended. He goes on to warn that making the distinction between regulation and punishment opens the door to further encroachments of liberty by a Congress that could pass laws that would confine people, if those laws are labeled “regulation.”

Dershowitz doesn’t discuss Rehnquist’s claim that the right to a speedy trial would prevent a non-convicted defendant from being incarcerated for excessively long periods. At least in the case of Salerno, Rehnquist was right. Salerno was detained for about eight months before he was convicted. Ironically, Dershowitz would have required proof at the 75th percentile to detain Salerno that long, the same standard of clear and convincing proof that Rehnquist proposed in the decision. In practice, Rehnquist and Dershowitz don’t really disagree about the details of the Salerno case.

The problem with Rehnquist’s decision, which Dershowitz leaves undiscussed, is that the right to a speedy trial is no real guarantee against very long incarceration without a criminal conviction. In the 1972 Barker v Wingo case, the Supreme Court ruled that the right to a speedy trial is fundamental, but there are no strict time limits. In practice, the courts do not protect a defendant from long pre-trial incarceration.

Dershowitz wants the courts to solve the problem of potentially long pre-trial detention by requiring that periods longer than a year would require a 90% proof standard. However, the history of the courts’ decisions shows that they are the wrong branch of government to look for a solution. The solution lies with the legislative branch.

Virginia has a speedy trial statute that requires that a trial must start within five months of a finding of probable cause if the defendant is held in custody. Florida also has a speedy trial provision that requires a trial to commence within 90 days for a misdemeanor and within 175 days for a felony. New Jersey, on the other hand, had no speedy trial rule or statutes before 2017. Defendants were routinely confined for many years awaiting trial. In many cases, evidence was weak, resulting in mistrials and further time in jail until the next trial. Even with the new speedy trial reform in New Jersey, involuntary confinement can last for two years and can be extended for various reasons.

Dershowitz’s proposals won’t help to mitigate the problem of long pre-trial detention. Strong speedy trial statutes are necessary for that.

Can Commitment Proceedings Be Distinguished From Criminal Proceedings?

Commitment to an Asylum

Dershowitz claims you can’t distinguish commitment from criminal proceedings, presumably because punishment is punishment, regardless of how it came about. This justification gives short shrift to a complex legal issue. In Addington v Texas, the Supreme Court ruled that clear and convincing evidence was the constitutionally required standard of evidence for involuntary commitment for medical reasons. The court reasoned that psychological evaluations are too uncertain to be submitted to a “beyond a reasonable doubt standard.” In the court’s view, imposing a reasonable doubt standard would create a burden that the state would almost never be able to meet. Addington v Texas highlights one compelling differentiating factor between civil and criminal proceedings: the nature of the evidence may be more inherently uncertain, making a beyond reasonable doubt standard infeasible in cases in which involuntary confinement can be greater than one year.

Besides, the power to institutionalize mentally ill people is founded on the principle that they are not competent to take care of themselves. Confinement to a mental health facility might feel just like punishment, but that doesn’t mean it is punishment. Confinement is sometimes an unfortunate but necessary byproduct of health care for the profoundly mentally ill.

Dershowitz’s proposal to use a beyond reasonable doubt standard for mental health commitments beyond a year directly contradicts what the court has already ruled—that a reasonable doubt standard is not possible for mental illness cases. Again, it is necessary to look to the legislatures to protect against excessive or unjust mental health commitment.

Confinement of Sexual Predators

Civil confinement of sexual predators is different, since the goal is not to protect the confined but rather to protect the potential future victims. For these cases, the court has essentially dismissed the reality of the tradeoff between false negatives and false positives that Dershowitz emphasizes, undercutting a key foundation of his argument. In Kansas v Hendricks, the Supreme Court upheld Kansas’s sexual predator law. The Kansas law included as a condition for confinement the inability to control illegal sexual behavior, implying that false positives must not be reasonably possible if someone is to be confined. Hence, there is no tradeoff to manage.

Numerical Standards of Proof

Currently, the reasonable doubt and other standards of legal proof are defined qualitatively by judges in jury instructions. Dershowitz is advocating that these standards be quantified. Some research indicates that quantification of legal standards of proof can lead to more consistency in juror decisions, raise the bar for conviction, and produce more clarity in how jurors understand the standards they are meant to apply. See for example here, here, and here. Dershowitz’s proposal to quantify reasonable doubt has some merit, although it’s very likely a quixotic goal. Despite the evidence that quantified standards of proof might be better, there are no signs that any courts are thinking seriously about doing it.

Dershowitz also wants to explicitly quantify the Blackstone ratio, but state courts and the Supreme Court have already done so. Pi, Parisi, and Luppi compiled cases from U.S. state courts and the Supreme Court in which the ratio was explicitly discussed or mentioned.

There is no consensus among the state courts, as the table above shows, and therefore no reason to believe that Dershowitz’s second quantitative proposal is not as quixotic as the first.

Summary

Dershowitz proposes to weaken the standard of proof in criminal cases, a rejection of a bedrock principle of American law

In civil cases, his proposals ignore the differences between criminal and civil proceedings that have already been established by the courts

Those precedents imply that Dershowitz’s civil proposals are irrelevant, since they could not be implemented without a profound rejection of foundational court decisions

Legislatures rather than the courts are best placed to protect innocent people from false civil confinements

Quantifying the standard of proof would be beneficial, but no court has shown any real interest in doing that

The large current disagreements among courts on the Blackstone ratio suggest that Dershowitz’s proposal to make it dependent on the potential length of confinement is not realistic