Should We Have the Right To Trial By Algorithm?

An AI jury could provide a fairer and more impartial verdict than a human jury

The right to be judged by a fair and impartial jury is a bedrock protection against unjust prosecution. And yet, we know the judicial system still makes mistakes. Since 1992, the Innocence Project has used DNA and other forensic evidence to identify and reverse over 250 convictions of innocent people. In 63% of its cases, an eyewitness misidentified the defendant and in 53% of the cases, the prosecution used bad forensic science. Wrongful convictions are also obtained because of false confessions, the testimony of unreliable jailhouse informants, an insufficient defense, improper prosecutorial or judicial conduct, and racial bias. Despite the significant legal protections defendants enjoy, human errors can overwhelm them, raising the possibility that algorithms might do better. AI jurors, which are not bedeviled by human prejudices and irrationalities, might provide fairer and more impartial verdicts than human juries.

How Much Do Legal Protections Matter in Practice?

The Innocence Project’s rate of exoneration is very small relative to the size of the incarcerated population: it averages a little over seven released prisoners per year, making it difficult to determine if the problem of false conviction is much bigger, but difficult to identify, or relatively small. A 2019 study estimated the rate of false convictions at about six percent overall, but as high as 40% in rape cases. The study assumed that if prisoners anonymously self-report their own innocence or guilt, they would be truthful, a doubtful premise. Six percent is therefore likely an upper bound estimate, but even if 3% are falsely incarcerated, that implies about 54,000 innocent people are serving jail terms, given that the total incarcerated population in 2025 is about 1.8 million people.

The argument that the false conviction rate is much smaller than 6% can be justified by the substantial legal protections conferred on defendants by the U.S. legal system:

Prosecutors are supposed to bring cases only when there is enough evidence for a jury to unanimously conclude that the accused is guilty beyond a reasonable doubt

The judge ensures that the defendant receives a fair trial

The accused has a right to be represented by an attorney if he can’t afford one

The prosecution must prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt; the defendant has the presumption of innocence

The jury must be fair and impartial, unanimously convicting the defendant

The defendant has the right to a speedy trial

The defendant has the right to receive a reasonable bail while awaiting trial

Based on these protections, you might dismiss the survey evidence as being heavily overestimated.

My own naivete that legal protections necessarily keep the false conviction rate low was shattered about a decade ago. In early winter 2016, I began to follow a homicide case in Trenton, NJ. In 2012, a corrections officer, Carl Batie, was murdered during a burst of gunfire while standing outside on a balcony at an Obama re-election party.

Carl Batie

Trenton police arrested Maurice Skillman in early 2013 and accused him of the murder. Later, they also arrested Hykeem Tucker and accused him of being a lookout. Both had previous convictions on serious drug offenses.

Maurice Skillman

Hykeem Tucker

I followed the trial daily by reading Trenton Homicide Watch, which gave thorough reports. As the trial progressed, I was surprised by how weak the prosecution’s case was: 1) no eyewitnesses to the shooting implicated the defendants; 2) no murder weapon was recovered; 3) no motive was offered; and 4) no physical evidence was discovered. The primary evidence presented was a dark and grainy video tape on which a police officer claimed he could identify the defendants, but no one else could. The tape does not show the figures shooting 22 rounds of 9 mm ammunition, even if Skillman and Tucker were the figures on the tape. If it were them on the tape, it would just prove that they were outside. I fully expected that the jury would acquit the defendants after no more than an hour’s deliberation.

But that’s not what happened. As Trenton Homicide Watch reported, the jury deliberated for several days and then finally passed a note to the judge with the question “Can we consider alternative theories?” The following day, the jury hung, and the judge declared a mistrial. Trenton Homicide Watch reported that there were rumors that a lone juror had refused to convict amid what the report labeled as “rancorous jury discussions.” But shouldn’t the rumors have been that a lone juror had failed to acquit?

What Happened in that Jury Room?

I followed that case so closely in the media because my wife was on the jury. She was not allowed to discuss the case at all, so I followed it on Trenton Homicide Watch. Every day she drove to a parking lot that collected the jurors to ride the bus to the court. On the day the jury hung, I got a call from her to come immediately and pick her up in front of the courtroom. When I arrived, she was accompanied by two armed court officers who had separated her from the other jury members. Some jury members had physically intimidated her, even physically threatened her. She had hung the jury, and so the jury wanted to hang her. She could not get on the bus with them. Once the trial was over, I would finally learn what happened.

Although the jury initially split 50-50 on conviction, there was a small contingent that argued very aggressively for conviction. They quickly overcame the objections of the other jurors with arguments such as

They are gang members. If they didn’t do this, they did something else. We have to get these gangs off our streets

You may not be able to identify the gang members in the video. But police officers are trained to identify criminals, and they know who the criminals are in Trenton

The defense didn’t prove that they were innocent

Those arguments had swayed all the jurors, except my wife, who stubbornly kept pointing out that there was no evidence, that the defense does not have to prove the defendants are innocent, and that there are reasonable alternative explanations of what happened based on the facts in the case, and so reasonable doubt exists. The small contingent told her that considering alternative explanations was “illegal” and that “she was breaking the law.” That’s why Trenton Homicide Watch reported that the jurors had sent a note to the judge asking if alternative theories were acceptable. Homicide Watch didn’t know that the jurors also tried to convince the judge to remove her from the jury for so-called “illegal” jury deliberations.

The judge didn’t expel her, but in a surreal action, he called the jury back into court. Instead of explaining that reasonable alternative explanations based on the facts of the case could create reasonable doubt, he instead sternly lectured that “Fanciful hypothecations (sic) play no role. Keep it real. This is the real world.” He also admonished the jury not to be “partisans.” With these instructions, the judge had signaled to the jury his own views on the case and had undermined my wife’s ability to argue that reasonable doubt existed. Despite the continuing pressure from the jury (and apparently from the judge), she refused to convict the two men on no evidence, and the jury hung.

What Failed in this Case? Everything

The Prosecution Failed

The prosecution’s strategy was just to keep Skillman and Tucker in jail and then retry them, which it did, convicting them in a second trial in June 2016. When I checked other cases, I found that prosecutors were routinely pursuing the same strategy. Shaheed Brown, who also had an extensive rap sheet, was accused of murder and tried three times, resulting in three hung juries. Brown’s case was even more absurd. The only evidence of guilt offered was that he was on the street when the murder occurred, and a witness thought he was wearing a black glove, which could have indicated that he wanted to hide gunpowder residue on his hand. The prosecution also alleged that by shaving his head and moving to Newark, Brown was trying to disappear. But other than that, no direct witnesses, no gun recovered, no physical evidence. Brown’s defense, besides pointing to the paucity of evidence asked, “why couldn’t the other guy on the street have done it?” On the prosecution’s fourth attempt, they changed the theory of the case to allege that the other guy did do it, and Brown was his accomplice. That case fizzled.

Shaheed Brown

Isaiah Greene also had three hung juries around that time. Instead of bringing strong evidence to cases, the prosecution was relying on its ability to keep trying cases until it got a conviction or had to give up. Double jeopardy doesn’t arise if a jury hangs. As long as there a few biased jurors who are determined to convict, regardless of the evidence, the prosecution’s “try ‘em until we fry ‘em” strategy will work.

Isaiah Greene

The Judge Failed

Besides undermining discussion of reasonable doubt and signaling his own views in the Skillman-Tucker case, the judge allowed the prosecution to put up a highly prejudicial picture of a Tek-9, a scary looking gun that the prosecution said “could” have been the murder weapon, even though no gun was found. Although it should have been obvious that there was no evidentiary value, the judge allowed the prosecutor to put on the witness stand in handcuffs Maurice Skillman’s twin brother, who was in jail serving a long sentence for murder. Skillman’s brother was belligerent and refused to answer any questions, as the prosecutor would have known he was going to do. The “guilt by association” imagery the judge permitted was invaluable to the prosecution. Finally, after he declared a mistrial, the judge prevented the press from interviewing the jurors, which many in the press claimed was illegal. My wife would have been happy to talk with the press.

The Defense Failed

The defendants were given court appointed lawyers who tried to do their best, but they were too understaffed with limited funds. They missed many opportunities to challenge the prosecution. For example, a police expert claimed the 22 9 mm shell casings found at the murder scene likely came from a Tek-9. In an inflammatory ruling, the judge allowed the prosecution to show the jury a picture of the Tek-9. But a Tek-9 magazine holds 20 rounds, two rounds too few. You can get a 32 round extended magazine for the Tek-9, but extended magazines that hold as many or more rounds are available for more common handguns, such as the Glock 19. The murder weapon did not have to be a Tek-9. It’s also not likely it was a Tek-9. The Tek-9 hasn’t been produced since 1994 and the company went bankrupt in 2001. Used Tek-9s are illegal in New Jersey. The grainy video did not show the figures carrying a large gun like a Tek-9 or any gun in fact.

The defense also did not rebut the police officer’s special ability to identify people at night in a grainy security video, especially when their own mothers could not have recognized them on the tape. The defense may have felt that it was the job of the prosecution to prove the police officer had an extraordinary ability to identify people, but we know that some on the jury believed (perhaps from watching tv shows) that the defense’s job was to exonerate the defendant.

Most importantly, the defense failed to identify and challenge jurors who were biased in favor of the prosecution during the jury selection process. That failure is likely one common denominator present in all the hung jury cases.

Reasonable Doubt Failed

Most of the jury didn’t understand the reasonable doubt standard in a criminal trial. The judge undermined the standard as well.

The Jury Failed

The jury had a small but zealous contingent of partisans for the prosecution. Failure to eliminate biased jurors in either direction increases the chance of a mistrial.

The Right to a Speedy Trial Failed

Skillman and Tucker were jailed for three years before they were convicted. Shaheed Brown was jailed for four years and not convicted.

The right to a speedy trial does not mean that you can’t spend a long time in jail. In the 1972 Barker v Wingo case, the Supreme Court ruled that the right to a speedy trial is fundamental, but there are no strict time limits. In practice, the courts do not protect a defendant from long pre-trial incarceration. State legislation does that.

New Jersey had no speedy trial rule or statutes before 2017. Defendants were routinely confined for many years awaiting trial. In many cases, evidence was weak, resulting in mistrials and further time in jail until the next trial. Even with the new speedy trial reform in New Jersey, involuntary confinement can last for two years and can be extended for various reasons. In contrast, Virginia has a speedy trial statute that requires that a trial must start within five months of a finding of probable cause if the defendant is held in custody. Florida also has a speedy trial provision that requires a trial to commence within 90 days for a misdemeanor and within 175 days for a felony.

The Right to a Reasonable Bail Failed

The defendants were given $1 million bail, an impossible financial burden for them to meet. They stayed in jail for three years before being convicted on the second try. Shaheed Brown was also given a $1 million bail. He was indicted in 2014 and remained in jail until after his third mistrial. He was released with an ankle bracelet in 2018 after the New Jersey speedy trial rules went into effect.

AI Jurors Can Potentially Do Better

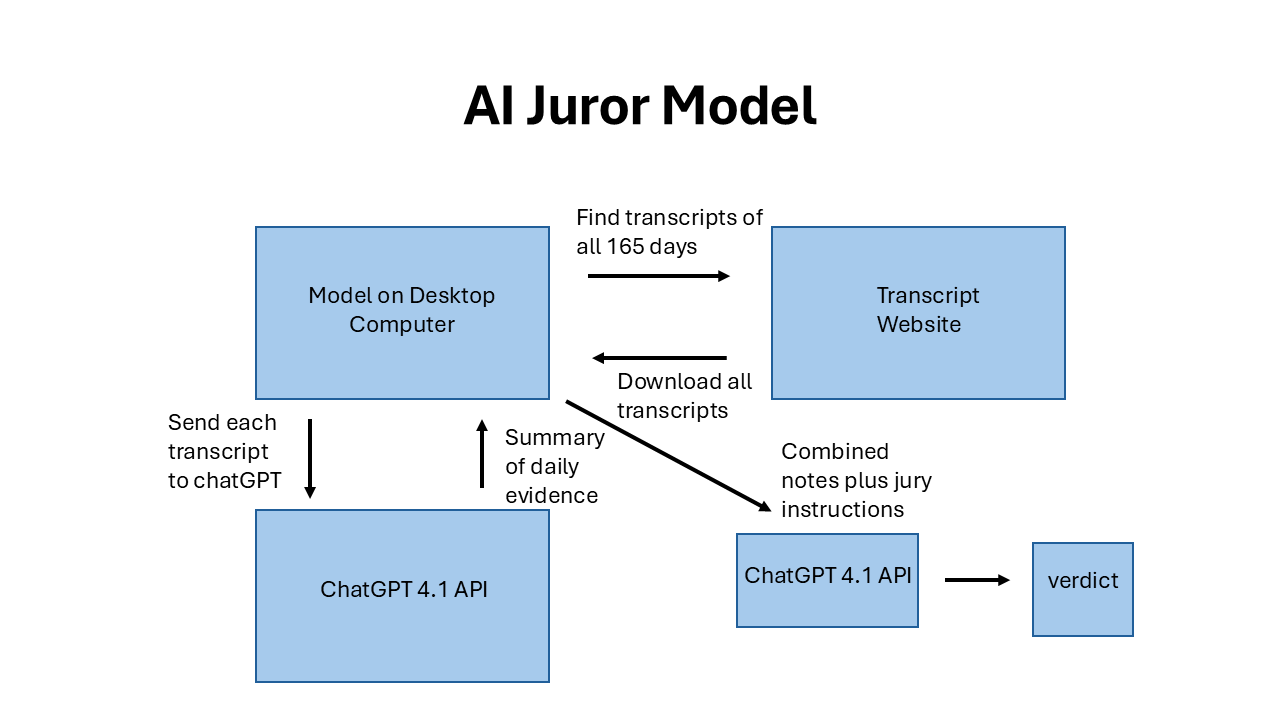

The human error in these New Jersey cases was massive. Can algorithms do better? To find out, I built a rudimentary AI juror, depicted in the diagram below. The model gathers evidence from a website, summarizes it, and then uses the summary to render a verdict. To test the model, I selected the OJ Simpson murder trial, since full daily trial transcripts are available. I followed the evidence very carefully at the time, concluding that an impartial decision should be not guilty under a reasonable doubt criminal standard and guilty under a civil preponderance of the evidence standard. What would an algorithm conclude?

The model goes to Jack Walraven's website and downloads each of the 165 daily trial transcripts, over six million words in total. Each transcript is then sent to the chatGPT 4.1 API, which takes notes and summarizes each day’s transcripts, keeping the most important evidence. The 165 days of notes are then assembled into juror notes of about 250,000 words, which is then fed back to the API for the model to deliberate and render a verdict. Here are the results under the criminal and civil standards of proof.

AI Juror Verdict on OJ Simpson Case

Below is a careful, impartial verdict for both cases, based solely on the detailed daily notes provided.

---

## **Case 1: Standard of Reasonable Doubt ("Better for ten guilty men to go free than one innocent man be convicted")**

### **Verdict: Not Guilty**

---

### **Reasoning**

**1. Reasonable Doubt Standard**

- This standard requires acquittal if there is any reasonable doubt about the defendant’s guilt, even if the evidence points toward guilt.

**2. Physical Evidence: DNA, Blood, Hair, Fibers**

- **DNA Evidence:** Multiple stains at the crime scene, in the Bronco, and at Simpson’s home matched Simpson, Nicole Brown, and Ronald Goldman. The statistical rarity of these matches is extremely high.

- **Chain of Custody/Contamination:** The defense raised substantial, specific concerns about LAPD’s evidence collection, documentation, and chain of custody:

- Evidence was sometimes left unsecured for days, with incomplete logs.

- Swatches and blood samples were not always counted, initialed, or tracked.

- The Bronco was left unsecured for months, with no log of who accessed it.

- The socks with Nicole Brown’s blood were not observed to be bloodstained by multiple examiners for weeks, and a "wet transfer" pattern was later found, suggesting possible post-collection contamination or planting.

- EDTA (a preservative found in blood collection tubes) was detected in bloodstains on the socks and rear gate, raising the possibility of blood from a reference tube being used as evidence.

- The defense's DNA experts (Gerdes, Speed) and the NRC report highlighted the risk of laboratory error, contamination, and the lack of blind proficiency testing.

- The prosecution’s own experts admitted that contamination or error could not be ruled out, and that the frequency statistics do not account for lab error or contamination.

- **Glove Evidence:** The gloves found at Bundy and Rockingham matched each other and were rare, but:

- Simpson was seen in court unable to fit into the gloves.

- The defense’s expert (MacDonell) demonstrated that blood exposure would not cause the gloves to shrink significantly.

- The chain of custody for the gloves was challenged, and the possibility of evidence planting was raised, especially given the conduct of Detective Fuhrman.

- **Shoeprints:** Only one set of bloody shoeprints (Bruno Magli, size 12) was found, matching Simpson’s size, but no evidence was found that Simpson owned such shoes, and no shoes were ever recovered.

- **Hair/Fiber Evidence:** The presence of Simpson’s hair and fibers at the scene is consistent with his prior access to the Bronco and the victims, and is not unique or definitive.

**3. Witness Credibility and Police Conduct**

- **Detective Mark Fuhrman:** Multiple witnesses and tapes proved he lied under oath about using racial slurs and expressed racist, violent attitudes and willingness to fabricate evidence. He invoked the Fifth Amendment when recalled. This undermines his credibility regarding the discovery of the glove at Rockingham.

- **Detective Vannatter:** The chain of custody for Simpson’s reference blood is questionable; he carried the unsealed vial for hours, did not refrigerate it, and did not book it promptly. At least 1.5 mL of blood is unaccounted for.

- **Crime Scene Handling:** Numerous lapses and mistakes were documented by both prosecution and defense experts, including the use of a blanket from inside the house to cover Nicole’s body (risking trace contamination), delayed evidence collection, and incomplete documentation.

- **Coroner’s Office:** Multiple mistakes and omissions in the autopsies, including failure to collect certain evidence and errors in documentation, though the chief medical examiner testified these did not affect the main conclusions.

**4. Timeline and Alibi**

- **Timeline Witnesses:** Multiple defense witnesses (neighbors, dog walkers, limo driver) provided testimony suggesting the murders occurred later than the prosecution’s timeline, potentially after Simpson had left for the airport.

- **Kaelin’s Testimony:** Kaelin could not account for Simpson’s whereabouts during the critical window, but did not see any injuries or blood on Simpson when he left for the airport.

- **Simpson’s Demeanor:** Multiple witnesses (family, friends, limo driver, flight crew) described Simpson as acting normally before and after the murders, with no visible injuries or signs of distress.

**5. Motive**

- **Domestic Violence:** There is strong evidence of a history of domestic violence, including prior incidents, 911 calls, and testimony from Nicole’s family and friends. This supports a possible motive but does not prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

**6. Alternative Theories**

- **Defense Theories:** The defense raised the possibility of evidence planting, contamination, and alternative perpetrators (e.g., drug-related motives), though these were not strongly supported by direct evidence.

---

### **Most Important Pieces of Evidence (for this standard):**

- **DNA evidence linking Simpson to the crime scene, Bronco, and socks.**

- **Chain of custody and contamination concerns for blood, socks, Bronco, and gloves.**

- **Fuhrman’s perjury and invocation of the Fifth Amendment.**

- **EDTA findings in bloodstains (suggesting possible planting).**

- **Timeline testimony from neutral witnesses.**

- **Absence of murder weapon, bloody clothes/shoes, or direct eyewitnesses.**

---

### **Conclusion (Case 1):**

While the physical evidence points toward Simpson’s involvement, the defense has raised substantial, specific, and credible doubts about the integrity of the evidence, the possibility of contamination or planting, and the reliability of key police witnesses. Under the strict "reasonable doubt" standard, these doubts are sufficient to acquit, as it is better for ten guilty men to go free than for one innocent man to be convicted.

---

## **Case 2: Standard of Reasonable Doubt ("Better for one guilty man to go free than one innocent man be convicted")**

### **Verdict: Guilty**

---

### **Reasoning**

**1. Reasonable Doubt Standard**

- This standard is less strict; the jury may convict if, after considering all the evidence, they are convinced of guilt beyond a reasonable doubt, even if some doubts remain.

**2. Physical Evidence: DNA, Blood, Hair, Fibers**

- **DNA Evidence:** Multiple bloodstains at Bundy, in the Bronco, and at Rockingham matched Simpson’s DNA, with statistical rarity estimates in the millions or billions. Nicole Brown’s blood was found on Simpson’s socks in his bedroom; Ron Goldman’s blood was found in the Bronco.

- **Chain of Custody/Contamination:** While the defense raised concerns about contamination and chain of custody, there is no direct evidence that contamination or planting actually occurred. All labs reported negative controls, and the same DNA profiles were found by multiple independent labs (DOJ, Cellmark, FBI).

- **Glove Evidence:** The gloves found at Bundy and Rockingham were rare, matched each other, and were consistent with gloves purchased by Nicole Brown for Simpson. Simpson was photographed wearing similar gloves. The fit demonstration in court is not conclusive, as the gloves had been exposed to blood, weather, and time, and experts testified they could shrink.

- **Shoeprints:** The only bloody shoeprints at the scene were from rare Bruno Magli shoes, size 12, matching Simpson’s size. No evidence was found that Simpson owned such shoes, but the rarity and size are compelling.

- **Hair/Fiber Evidence:** Simpson’s hair was found in the knit cap at Bundy and on Ron Goldman’s shirt; blue-black cotton fibers consistent with Simpson’s clothing were found on multiple items.

**3. Witness Credibility and Police Conduct**

- **Detective Mark Fuhrman:** While Fuhrman’s perjury and racism are deeply troubling and undermine his credibility, the glove evidence is corroborated by other detectives and physical evidence. The defense’s theory of planting is speculative and not supported by direct evidence.

- **Detective Vannatter:** The handling of Simpson’s blood was sloppy, but there is no direct evidence that the blood was used to plant evidence. The amount of unaccounted blood is small and could be explained by laboratory loss.

- **Crime Scene Handling:** While there were mistakes and lapses, there is no direct evidence that these resulted in contamination or planting of key evidence. Multiple labs, using different methods, obtained consistent results.

**4. Timeline and Alibi**

- **Timeline Witnesses:** The defense’s timeline witnesses were inconsistent and sometimes contradicted each other. The prosecution’s timeline, supported by the barking dog witnesses and the limo driver, places Simpson unaccounted for during the likely time of the murders.

- **Kaelin’s Testimony:** Kaelin could not account for Simpson’s whereabouts during the critical window; his testimony about the "thumps" is consistent with Simpson returning to the property after the murders.

- **Simpson’s Demeanor:** While some witnesses described Simpson as acting normally, others noted he was sweating, rushed, or agitated after the murders.

**5. Motive**

- **Domestic Violence:** There is overwhelming evidence of a history of abuse, jealousy, and control, culminating in Nicole’s decision to end the relationship. This provides a strong motive.

**6. Alternative Theories**

- **Defense Theories:** The defense’s alternative theories (e.g., drug-related murders, evidence planting) are speculative and unsupported by direct evidence.

---

### **Most Important Pieces of Evidence (for this standard):**

- **DNA evidence matching Simpson at multiple key locations (crime scene, Bronco, socks).**

- **Simpson’s blood at Bundy and in Bronco; Nicole’s blood on Simpson’s socks; Goldman’s blood in Bronco.**

- **Bloody shoeprints matching rare Bruno Magli shoes, size 12.**

- **Hair and fiber evidence linking Simpson to the crime scene and victims.**

- **Timeline evidence placing Simpson unaccounted for during the murders.**

- **History of domestic violence and motive.**

---

### **Conclusion (Case 2):**

While there are legitimate concerns about police conduct, chain of custody, and some procedural errors, the totality of the physical evidence—especially the DNA matches, blood evidence, and timeline—overwhelmingly supports Simpson’s guilt. The defense’s contamination and planting theories are speculative and not supported by direct evidence. Under the less strict "reasonable doubt" standard, it is reasonable to conclude that Simpson is guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.

---

**Note:**

This verdict is based solely on the evidence and testimony summarized in the daily notes, applying the two specified standards of reasonable doubt.

The AI juror did an excellent job judging the OJ case. It was able to read through six million words of testimony and render a verdict in about an hour or so, much faster than a human juror, and at a cost of between $15 - $20, much less than the daily rate of pay for a human juror, not to mention the other much larger court costs.

AI Juror Verdict on the Skillman-Tucker Case

Now let’s try the model on the Skillman-Tucker case. The trial transcripts aren’t available online, but the Trenton Homicide Watch coverage provides a fair summary of the evidence presented by the prosecution and defense. The model pulls the reports from the website and then renders a verdict almost immediately—we don’t have to wait for days.

Verdict

Maurice Skillman (murder): Not Guilty

Hykeem Tucker (murder under accomplice liability): Not Guilty

Why

1) Identity of the shooter isn’t proven beyond a reasonable doubt

The State’s core ID rests on Det. Peterson’s interpretation of grainy surveillance—a few seconds in a top corner, partly obscured, with a “small spark.” A defense expert (Boyell) explained why that “muzzle flash” could plausibly be something else and why the video quality/handling (camcorder transfer; no original DVR clone) limits reliability. That leaves substantial uncertainty about what the video actually shows and who it shows.

The only direct clothing description from a security guard (Feliciano) was a gray hoodie on the shooter, while Skillman was arrested that night in a black hoodie and gray pants. That mismatch is not trivial; it undercuts the State’s specific identification.

No witness provided a clear, independent, in-person identification of Skillman firing a gun.

2) No physical/forensic tie to either defendant

No murder weapon recovered.

No DNA, fingerprints, or other forensics tying Skillman or Tucker to a weapon, shell casings, or the shooting itself.

DNA on a recovered Giants cap matched someone else (Edward Acosta), not either defendant. Even if that cap is only peripheral, it underscores the lack of a forensic link to the defendants.

3) Alternative-suspect and alternative-item evidence create reasonable doubt

Shaquel Rock threatened to “shoot up” the event after being refused entry. He was later eliminated based on height/clothing, but the defense highlighted that investigators found a varsity jacket and gray/blue hoodies in a car tied to Rock’s cousin—items resonant with the State’s narrative of a varsity jacket and a gray hoodie in play. This doesn’t prove Rock (or his associates) did it, but it does open a plausible alternative path that the State did not close.

Given the already-weak video identification, those unresolved leads increase doubt about who actually fired.

4) Investigative gaps weaken the State’s theory

Impala not searched at the time it sat in the lot; later retrieval is unknown. If the State’s theory is the gun was stashed in a vehicle, not searching the obvious candidate leaves a hole.

Report/notes discrepancies (what made it into the 33-page report vs. notes), and failure to secure the original surveillance hard drive, cut against confidence in the reconstruction.

Off-duty officers recognized the defendants entering earlier (placing them at the scene), but presence ≠ guilt, especially without corroborating physical evidence.

5) Ballistics prove a rapid single-gun burst—but not whose gun

The TEC-9 analysis and 22 casings (with most matched to one weapon) fit the mechanics of the crime. They do not connect that gun to either defendant. Without a weapon, GSR, or possession evidence, the ballistics do not carry the identity burden.

6) Accomplice liability for Tucker isn’t met

To convict Tucker as an accomplice, the State must prove he knew of and intentionally aided the shooting. The evidence places him at the venue and in the general orbit of Skillman, sometimes outside; it does not firmly show lookout behavior or prearranged coordination with knowledge of a planned shooting. The “varsity jacket” identification is itself entangled with the alternative-suspect items, and the video is ambiguous. That leaves more than a reasonable doubt about intent and knowledge—both required for accomplice liability.

7) The burden standard controls the outcome

The court’s standard instructs that an honest, reasonable uncertainty after full consideration requires acquittal. Here we have:

Ambiguous surveillance and contested “muzzle flash.”

Clothing mismatch with the sole shooter description.

No gun, no forensic tie.

Unresolved alternative-suspect facts and items.

Investigative gaps.

Taken together, this does not leave me firmly convinced of guilt for either defendant.

Final note

This verdict does not say the defendants are factually innocent. It says the State did not meet its burden to eliminate reasonable doubt on identity (for Skillman) and on knowing assistance/intent (for Tucker). Under the law we were given, that requires Not Guilty on the murder charges.The AI juror produced a well-reasoned and, in my view, correct verdict.

AI Juror Verdict on the Shaheed Brown Case

Now let’s try the Shaheed Brown case, in which the human jury hung three times.

Verdict: Not Guilty

Why (under “beyond a reasonable doubt”)

First, a quick clarity note: the evidence you’ve provided is about the 2014 shooting of Enrico Smalley Jr. outside La Guira Bar. My verdict below is based solely on the Smalley case facts you supplied.

1) Identification of the shooter is uncertain

No witness credibly and consistently identifies Brown firing the gun.

Melissa Brown saw muzzle flash but did not identify the shooter; her location at the time is disputed, and the video to impeach her could not be authenticated in court.

Kenneth Crawford’s 911 “excited utterance” description (dreadlocks, light shirt, shooter standing over the victim) initially seems incriminating, but he later admitted his view was obstructed and that he mistook the victim for the shooter after reading news. That undermines the reliability of his account.

Surveillance video does not show Brown firing a gun. It shows proximity to Smalley and Brown wearing a black glove at times—but no clear image of a gun in Brown’s hand, and the detective conceded critical moments were inconclusive.

2) Forensics and physical evidence don’t tie Brown to the shot(s)

No firearm recovered, no gunshot residue, no fingerprints, no DNA linked to Brown.

Shell casings: five Tulammo and one Winchester. Mixed brands can be read multiple ways (one shooter with mixed ammo or multiple shooters). This does not pinpoint Brown.

The defense argument about casing pattern/angle suggesting a shooter position inconsistent with Brown’s location was not definitively refuted by the State’s expert testimony in your account.

3) Third-party/alternative-shooter doubt is plausible

Alvie “King” Vereen steps off camera for ~4 seconds immediately before the shots and may appear to tuck something into his waistband after. The lead detective called this inconclusive, but it creates reasonable doubt, especially with:

Multiple men reportedly wearing black gloves (Hedgepath couldn’t ID two of them).

The possibility—raised by casing brands and movements on video—of more than one armed person present.

The defense’s broader third-party-guilt case (including Rodney Sutphin) was constrained by rulings; while constraints don’t prove Brown’s innocence, they limit the State’s ability to dispel reasonable alternative scenarios within what the jury actually heard.

4) Motive and “consciousness of guilt” are suggestive but not enough

Motive (prior altercation) is weakly supported: testimony doesn’t clearly place Smalley at the earlier incident.

After-the-fact behavior (leaving for Newark, shaving head) can suggest guilt, but it’s ambiguous—the defense offered explanations (e.g., apartment not abandoned, bank/casino cards left, people present at the residence). Without stronger direct/forensic ties, these behaviors cannot carry the State’s burden by themselves.

5) Credibility limitations in key testimony

Hedgepath places a glove on Brown and supplies motive context, but he has felony priors and a deal (probation vs. prison) creating incentive to please the State. His testimony supports suspicion, not certainty.

Crawford is the State’s “star witness,” yet his trial testimony (obstructed view, misidentification risk) undercuts his earlier 911 description.

Bottom line under the standard

The State’s case is entirely circumstantial, lacks a weapon or direct forensic tie, and features equivocal video plus inconsistent eyewitness accounts. Given a credible alternative-shooter theory that the State did not definitively exclude, I am not firmly convinced beyond a reasonable doubt that Shaheed Brown was the shooter.

Accordingly, applying the instructions you provided—when left with honest, reasonable uncertainty—I must give the defendant the benefit of that doubt: Not Guilty.The AI juror found Shaheed Brown not guilty, again in a well-reasoned and well-supported decision. Three mistrials were not necessary to free him.

The AI juror model, which is based on the underlying LLM, performs very well out of the box. It could obviously be improved by fine tuning and by providing access to tools to avoid common probability fallacies, such as the prosecutor’s fallacy, that plague human trial decisions.

Innocence Project: AI Edition

Of course, the three Trenton cases I discussed are anecdotal. The cases show that legal protections don’t necessarily protect people from unjust prosecutions, but they also don’t demonstrate the problem is widespread or systemic. With over 1.8 million people currently incarcerated, how could we possibly sift through the evidence for each one to determine whether there are grounds to allege a false conviction?

AI jurors could sift through millions of trial transcripts, forming their own judgements, which could then be compared with jury verdicts. Suspicious verdicts could be pulled out for further review and potential legal follow up. AI models could examine the judges’ decisions for signs of reversible error as well as analyze expert testimony.

The barrier to this AI review is data. AI jurors need the complete trial transcripts for each case, which are not readily available online. In principle, the transcripts could be obtained, but not without time and cost. Going forward, all jurisdictions should post trial transcripts online, so that the public can check the fairness of the judicial process using algorithms.

Should Defendants Have a Right to Trial by Algorithm?

The Trenton cases show that a defendant can potentially benefit from an algorithm judging the facts of his case. If you can’t afford a good lawyer, have a prior criminal record, and live in a crime-infested city, you might be better off having an AI juror judge your case. In fact, the right to trial by an AI jury might deter a prosecutor from indicting you in the first place if he has little or no evidence. If we could quantify the true false conviction rate nationally using algorithms, and if it turns out these Trenton cases are not unusual, the demand to use AI jurors in the legal system will build.